Developing, Testing, and Deploying Efficient MCMC Algorithms for Hierarchical Models Using R

Daniel Turek

My name is Daniel Turek, and I'm an Assistant Professor in the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at Williams College. My area of research is computational statistics and algorithms, frequently with applications in ecological statistics. The workflow I describe is the process, from idea inception to publication, of creating an automated procedure to improve the sampling efficiency of Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. MCMC is an accessible and commonly used statistical technique for performing inference on hierarchical model structures.

Workflow

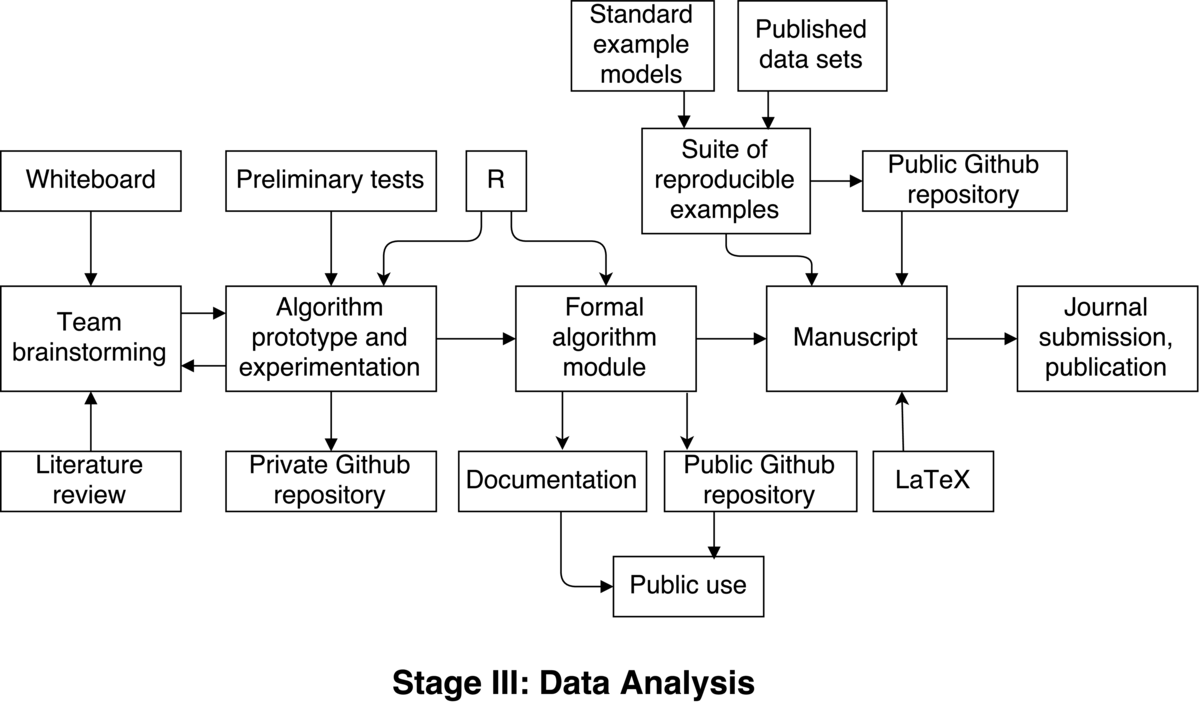

The process begins with team brainstorming of how an automated procedure for improving MCMC efficiency could work. This is arguably the most fun part of the entire process. This involves anywhere from two to four people actually hitting the whiteboard to discuss ideas. Each of several sessions lasts a few hours. We review theory and literature between these sessions, too. This initial exploration occurs over one or two weeks.

The process begins with team brainstorming of how an automated procedure for improving MCMC efficiency could work. This is arguably the most fun part of the entire process. This involves anywhere from two to four people actually hitting the whiteboard to discuss ideas. Each of several sessions lasts a few hours. We review theory and literature between these sessions, too. This initial exploration occurs over one or two weeks.

A plausible idea is hatched, and now must be prototyped to assess effectiveness. The project lead implements the algorithm in R, since our engine for doing MCMC runs natively there. This works well for our team, since everyone is comfortable in R, and code may be shared and reviewed easily. We create a private GitHub repository where members of our team write/review/modify the algorithm. This is a private repo amongst us, since it’s entirely experimental at this point, and not intended for the public. There is little (or no) documentation at this point.

Multiple iterations are possible at this stage, whereby ideas are implemented and undergo preliminary testing. Depending on the results of each iteration, we go back to the drawing board several times to figure out where the previous algorithm failed, or how it can be improved. Once again, we implement an improved version and test it using a small number of tests we’ve devised. This part of the process is time consuming, and potentially frustrating, as many dead-ends are reached. The path forward is not always clear. This process of revising and testing our algorithm may take three to six months.

Eventually, this process converges to a functional algorithm. All members of our team are satisfied with the results, and agree the algorithm is ready for a more professional implementation and hopefully publication.

One or two team members (those closest with the MCMC engine) do a more formal implementation of our algorithm. This implementation is added to an existing public GitHub repository, which contains the basis of the MCMC engine for public use. This step should only take a few weeks, since the algorithm is well-defined and finalized. Appropriate documentation is also written in the form of R help files, which are also added to the public repo.

The next goal is to produce a published research paper describing the algorithm and results. Towards this end, we assemble a suite of reproducible examples. These come from known, standard, existing models and published datasets, which are chosen as being either “common” or “difficult” applications of MCMC. A new public GitHub repository is created, and these example models and datasets are added in the form of R data files. Additionally, bash scripts for running our new algorithm on these examples are added, and also a helpful README file. The sole purpose of this repo is to be referenced in our manuscript, as a place containing fully automated scripts for reproducing the results presented in the manuscript.

Our reproducible examples include fixing the random number generator seed in the executable scripts, thus we can guarantee the same sampling results for each MCMC run (otherwise, a stochastic algorithm). However, the exact timing of each MCMC run will vary between runs and computing platforms, and hence the final measure of efficiency will vary, too. Thus, the exact results are not perfectly reproducible, but vary approximately 5% between runs.

Team members jointly contribute to drafting a manuscript describing our new algorithm, which presents the results from the suite of example models. This is jointly written by team members using LaTeX. The manuscript specifically references the repository of reproducible examples, and also explains the caveat in exact reproduction of the results — namely, that they will vary slightly from those presented, and why. The reviewers are nonetheless thrilled with the algorithm and reproducible nature of our research, and readily accept the manuscript for publication.

Pain points

The iterative process of devising and testing our algorithm is not well-documented or particularly reproducible. The only saving grace is that GitHub is used for versioning control, so in theory we could look backwards at previous work, if necessary. But in practice, the commit messages are short and not very descriptive, since everything is experimental at this point. No less, there’s basically no documentation accompanying our code. It would be difficult to actually review previous versions of the algorithm or results, if it were necessary.

In addition, the fact that our set of “reproducible” examples are not perfectly reproducible is a small point of contention. We are conflicted to call these examples reproducible, since the results presented in our manuscript cannot actually be recreated. Team members agree that this appears to be unavoidable. We explain this in the manuscript, and call our results “reproducible” nonetheless.

For preparation of our manuscript, numerical results are manually typed into a tex document. Tools such as knitr and sweave exist for automating this process, which automatically incorporate numeric and graphical results directly from R into LaTeX. We opted not to use these tools to automate the interaction between R and our manuscript, since not all team members are familiar or comfortable using these tools. Preparation of the manuscript would have been simpler and less error-prone had we used these tools, which probably would have been a wise decision, but the learning curve deterred our team from doing so.

Key benefits

The most notably reproducible aspect of this project is the public repo containing input data and scripts for re-running all analyses appearing in our manuscript. This includes individual bash scripts for running each particular analysis, as well as a single “master” script which re-runs all analyses. A reviewer can easily reproduce (to within a small margin of error) all numerical results appearing in the manuscript, and researchers reading the ensuing publication have an easy path forward to using the algorithm themselves.

Questions

What does "reproducibility" mean to you?

In the context of my case study, reproducibility means that users / reviewers can re-create the results (improvements in MCMC efficiency) presented in our manuscript. However, the results will not match exactly due to small differences in algorithm runtime.

Why do you think that reproducibility in your domain is important?

Reproducibility is important so that others may verify the results given in our publication. This ensures that the results are genuine, and also gives a clear path forward for others to use our algorithm.

How or where did you learn about reproducibility?

Mostly through the use of GitHub, from colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, and through general programming experience. No specific classes or workshops come to mind.

What do you see as the major challenges to doing reproducible research in your domain, and do you have any suggestions?

In the area of computational statistics, there are not many barriers to reproducible research aside from ignorance or technical inability. However, this case study does highlight one genuine obstacle: that of performance differences between various machines and computing platforms, which will affect algorithm runtime, which factors into our measure of efficiency.

What do you view as the major incentives for doing reproducible research?

Primarily so that others may actually (and easily) verify our results, if they so choose.